Understanding loss and grief

Loss and grief are both part of everyone’s experience as a human and also unique to who you are and what your loss means. Whether we’ve lost someone we love, a meaningful identity, the kind of parents we hoped for, or a future we worked towards but remains out of reach, our brains respond in powerful ways. Understanding how our brains respond to and process loss can often help us make sense of this intense experience.

What is Loss?

To talk about grief, we need to start with loss. Loss is the absence of something. It happens when we no longer have someone or something significant in our lives. While death is often the first thing we think of, we can also lose health, relationships, dreams, routines, roles, stability, meaning, or belief systems.

There are three categories of loss:

Defined Losses have a clear ending (e.g., death, moving).

Ambiguous Losses are unclear or ongoing (e.g., dementia, estrangement, chronic illness, unmet childhood needs).

Includes Anticipatory Losses that haven’t happened yet but we know are coming (e.g. terminal illness)

How Our Brains Process Grief

When we experience loss, our brains don’t automatically lose the neural pathways they formed to help us understand and relate to that which was lost. This means that when we experience a loss, our brain must “remap” space, time, and closeness. The result is grief: our brain’s way of remapping itself and adjusting to this change—an intense, painful process.

It is intense and painful for a few reasons:

Our brain’s attachment & reward systems get impacted: We’re wired to seek out the people and things we love. When they’re gone, the brain still searches for connection, creating waves of yearning and longing.

The parts of our brain connected with memory and emotion get confused and need to adjust: The hippocampus and amygdala hold our memories and emotional connections. This creates inner tension between knowing someone is gone and still feeling their presence.

Our stress response gets activated in addition to all the other emotions: Grief activates the body’s stress system. We might feel exhausted, irritable, shut down, or out of sync physically, as our body tries to adjust.

How it works is that when our brain runs into a reminder of the loss, it activates the intense and painful remapping process (i.e. grief) which can then help our brain rewire itself to understand and adjust to the new reality we live in without that which was lost. With time and support, if we are able to allow grief and ride its waves, it will help our brain leverage its neuroplasticity to rewire our internal maps and make space for new experiences alongside the pain. At the end of the day, grief is really a full-body, re-learning process that our brain is going through - relearning what reality is now that the loss has occurred.

Defined Loss

Defined loss is when something that exists no longer exists and this is very clear and defined. Though this is the kind of loss we often think about the most, it is less commonly experienced than ambiguous loss and grief (more about that below). This is because it’s often a larger, more intense one-time loss (e.g. someone dying, a house burning down) that requires a lot of initial effort to to cope with and adjust to in the short-term. It’s not easier than ambiguous loss (and vice versa) it is just different and our brain responds differently to the nature of this loss

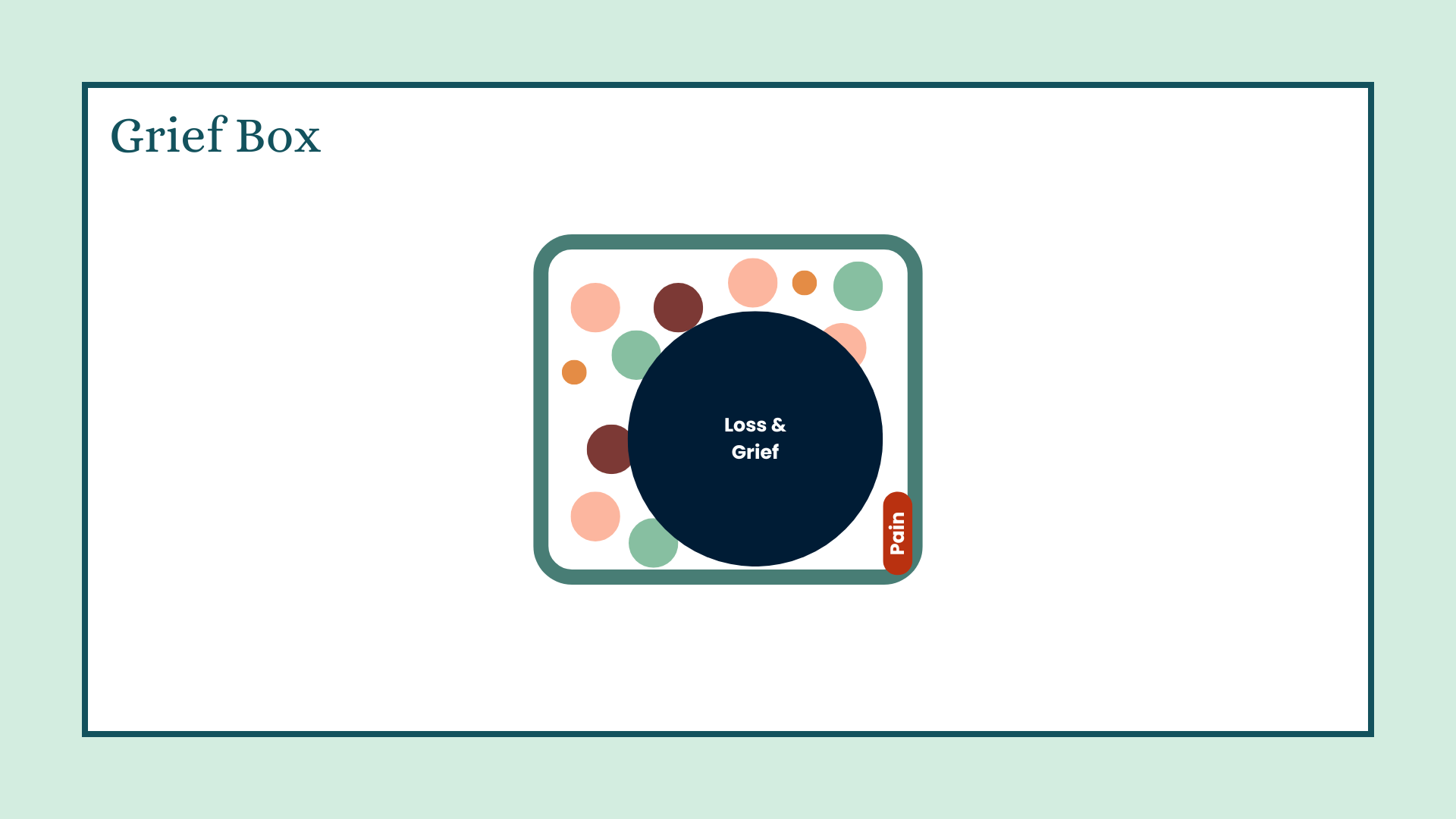

The “Grief Box” Metaphor

A helpful metaphor to use when thinking about how our brain processes defined grief is the “Grief Box”. Imagine your life as a box with a pain button inside.

In early grief (when the loss is still new), the grief ball is huge and hits the pain button constantly.

Over time, as we allow ourselves to feel and process grief, and continue to have new experiences, the grief ball remains the same size but the box grows and the grief ball hits the pain button less often.

This metaphor helps us see grief not as something we "get over," and never feel again, but something we learn to live with and manage when it gets activated.

Supporting Our Brain Through Grief

Certain practices are particularly helpful in allowing our brain to engage in its remapping process. These won’t make the process go faster, but they can help your brain not take longer than needed to engage in remapping:

Practice gentleness in response to your self-impatience – Remapping reality is a slow process. There’s no shortcut through it and elements of it will continue throughout your life. Trying to resist it or hurry it up can often make it go longer. It’s understandable that you want it to hurry up - it’s quite uncomfortable. And, validating that while also extending yourself patience and understanding can be helpful.

Care for your body – Sleep, regular movement, and soothing are the Tylenol/Ibproufen your brain needs when it is grieving.

Train your attention – Take time to intentionally acknowledge and register that as your brain processes the loss and experiences the pain of grief, there are also meaningful and enjoyable parts of your life as well. Training your brain to pay attention to both (rather than one or the other) can help you regrow your “box” so that the grief is hitting the pain button less often and when it does you feel more buoyed.

Reconnect with meaning – Engage in activities that give your life richness and purpose.

Practice self-kindness – Remind yourself: This is hard, and I’m doing my best. This includes kindness when you’re struggling to be kind and patient with yourself, “It’s hard to be kind right now, and the fact that I’m trying matters in the long run.”

Ambiguous Loss: When Closure Isn’t an Option

Ambiguous loss is a bit different from defined loss. Because the loss isn’t defined, the brain’s remapping process needs to be more of an ongoing process - remapping more constantly because the losses are happening more frequently.

We often experience ambiguous grief more than we realize because it is the kind of grief our brain engages in whenever we experience any kind of change. Though these losses may not be at the scale as a defined loss, they still end up requiring a lot of energy over time - a thousand papercuts over time vs a big gash.

What ends up happening is that if we’re not aware of it and caring for it, our brain stays stuck: both trying to remap an ongoing loss AND trying to get rid of or resolve an ongoing process because it is full of unknown (and our brain has not yet evolved in its natural state to deal helpfully with the unknown - we have to train it to do this). This can lead to exhaustion, rumination, confusion, and feelings of guilt for grieving something that’s “not really gone” (remapping the ongoing loss) and that “Something’s wrong with me for continuing to struggle with this” (trying to get rid of the distress that the unknown activates in our brains by blaming ourselves to feel more in control of it, and thus less unknown).

Unlike defined grief which gets triggered less often over time, ambiguous grief is more like an ongoing set of triggers - like ongoing waves in the ocean rather than a one-time tsunami.

Using the grief box metaphor, something can happen and your ambiguous loss gets triggered, it’ is the ball of grief suddenly growing larger when new changes or reminders occur—like it did at the beginning.

We can still do the same work to grow the box, we just need to do it more frequently and for longer than we do when we experience a defined loss.

Important Considerations for Ambiguous Loss:

Let go of the myth of closure if needed: Trying to get closure or resolution may increase our suffering when we’re experiencing ambiguous/ongoing losses and grief. It can sometimes be more helpful to take a long-term management approach where the goal is to ride the waves when they come rather than put energy towards changing circumstances.

Honor mixed emotions: You can feel both hope and sorrow.

Set boundaries with worry: Choose when to reflect, and when to pause. Worry containment can be helpful. Set a time each day for “worry time”. Then when the worries come up during the day, make a note and tell your brain you’ll revisit it during worry time. Then during that time, revisit those notes to see if you still need to worry about it or deal with it.

Create rituals: Acknowledge both what’s gone and what remains.

Connect with others: You are not alone in this. Either tell people what you’re experiencing or seek out groups of people who have a similar experience. It can be very helpful for your brain to receive data from other people’s experiences that can help it see that you’re not uniquely strange or bad as you struggle with this.

Anticipatory Grief: When Grief Comes Before the Loss

A subset of ambiguous loss and grief is anticipatory loss and grief. Because grief is how our brain remaps reality given a loss, when we anticipate a loss, the grief starts before the loss is final—when a loved one is dying, a relationship is ending, or a big change is coming. The brain begins its “remapping” process before the loss fully happens, which can lead to that confusing mix of emotions which are a trademark of ambiguous loss and grief: sadness, guilt, numbness, or even hope. It's normal to feel like you're on an emotional roller coaster because someone/thing is still here and yet our brain knows it will not always be this way.

Practices that can help:

Name and allow your emotions.

Stay connected to the present moment, what or who is here right now.

Practice self-compassion.

Balance preparation with moments of joy and savoring the goodness of what is.

Seek support from loved ones or professionals.

What About Complicated Grief?

In some cases, grief becomes so intense and persistent that it interferes with life and becomes a diagnosable mental illness. This is known as complicated grief. It often arises from ambiguous losses or defined losses that remain unprocessed. Signs include:

Grief that feels just as intense six months later

Difficulty engaging in daily life

Intense longing or guilt

A sense that life has lost meaning

If this sounds familiar, reaching out to a therapist can be particularly helpful.

Grief is a process of the brain reconfiguring what it understands about reality and then learning how to live with the new facts. Defined or ambiguous, anticipatory or here-and-now, grief is the experience of our body going through significant change after something has been lost. And, in this experience, it reveals the deep love, meaning, and connection that made the loss so hard in the first place.